How are the papers marked? How fair or strict are the markers? What should pupils do for a good result? PSLE science chief marker Jay Mahardale tackles these issues and more.

SINGAPORE: As the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) science chief marker for the past five years, Jay Mahardale has noticed something rather encouraging about the way the exam papers are marked.

There is acknowledgement on the markers’ part that there are alternative answers to different kinds of questions, he said.

Take, for example, a question involving spectacles and water: When the wearer comes out of a cold environment, the glasses will mist — but why do the water droplets disappear after some time?

“We’re looking out for … the key concept, which is about water evaporating,” said Mahardale, who is also the principal of Northland Primary School.

“But if a student is able to show that water gains heat and turns into water vapour, they don’t need to use the term ‘evaporate’. They can just show the understanding (of) the concept.

“We now honour a lot more of our students’ responses. … That’s really a plus point.”

The word “honour” often cropped up when he sat down with CNA Insider to share marking insights and exam tips as well as tackle the issue of how fair PSLE markers are. The interview is part of a series of digital-exclusive clips under the programme Regardless of Grades.

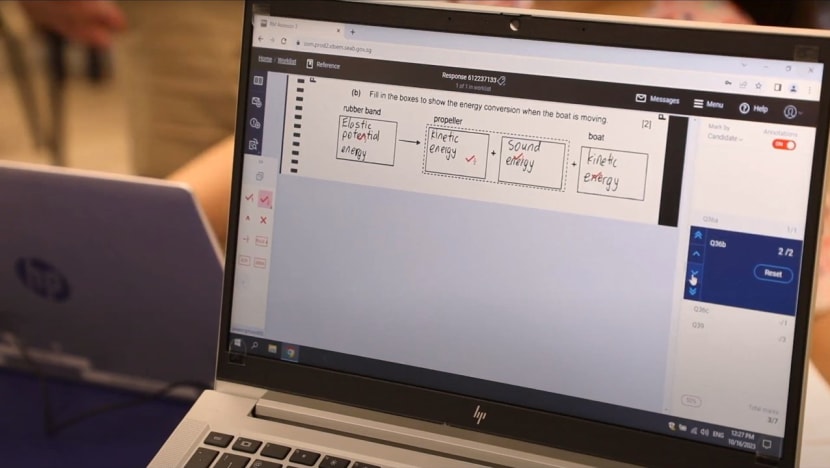

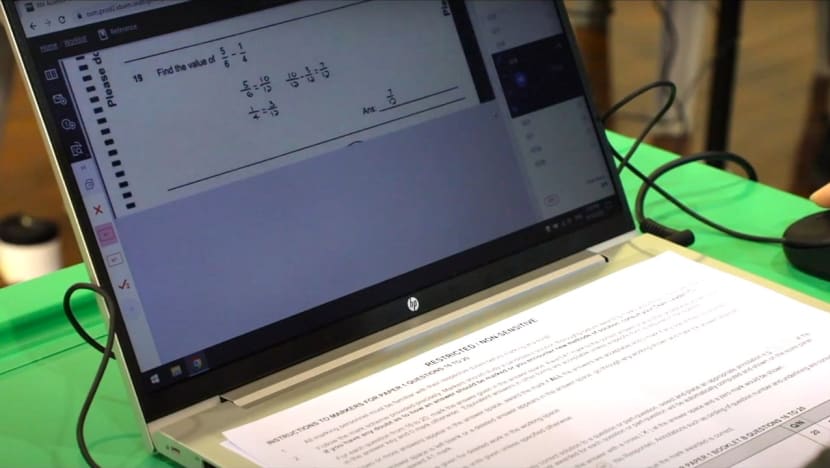

And it is not only science markers who accept alternative responses, he said. This is also the case in mathematics, which is taught in Singapore’s primary schools using the model method.

“Some of our students are able to express their solution through a different method, such as using algebra. And I think we want to honour our students’ responses,” he said.

So long as the methods are mathematically sound, “we’re able to give them the marks for that”.

WATCH: How to score in PSLE? Chief marker shares marking insights, exam preparation tips for students (15:02)

As he lifted the veil on the marking process, Mahardale answered these 10 questions that may be on the minds of parents and pupils alike:

The preliminary marking scheme is conceptualised by the chief exam setter.

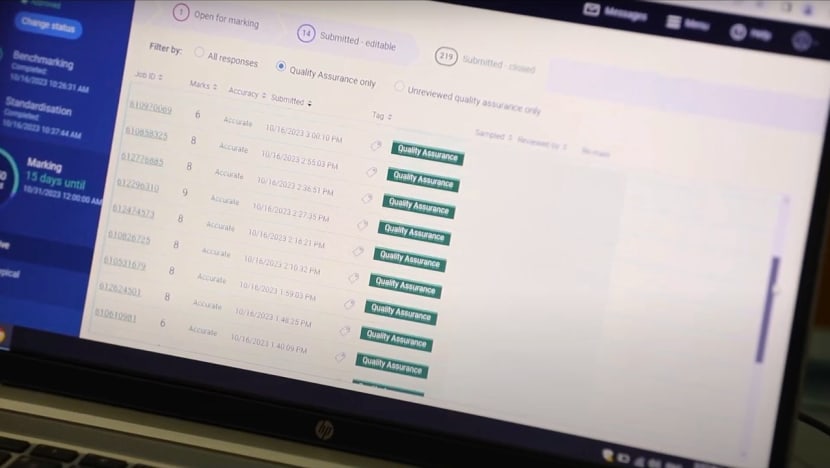

There is then a standardisation meeting at the Singapore Examinations and Assessment Board (SEAB) with key personnel such as chief markers at the PSLE marking centres, which will cover the “possible, acceptable and non-acceptable answers as well”.

“We also take a look at students’ sample scripts, just to have a sense about how students may respond to the questions,” said Mahardale. “Then we’ll decide on (how to update) the marking scheme.”

While the sample scripts are chosen randomly, “we have a good spread of responses from different schools”, he added.

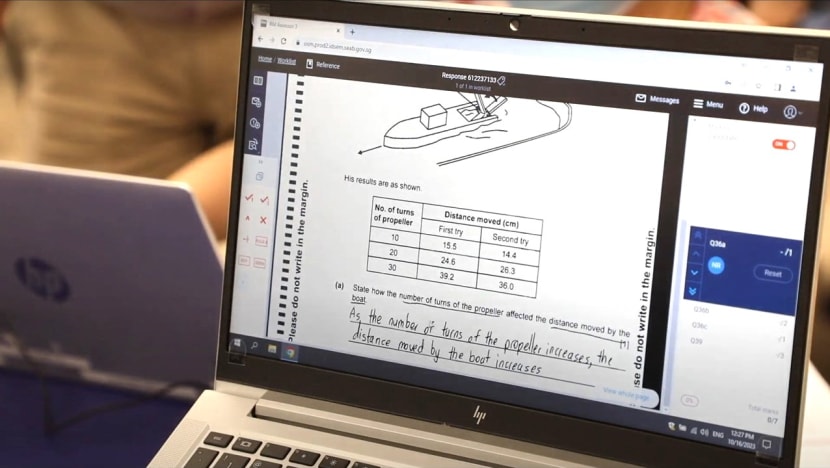

Once the marking scheme is finalised, the key personnel will go through it with markers at the marking centres. And all the marking is done online now; the scripts are scanned and uploaded to an on-screen marking system.

To help ensure consistent, accurate and fair assessment, PSLE markers are given a practice session with scripts pre-marked by the chief marker.

“Once the teachers try out the questions, it helps them to … have a good understanding (of) how to be consistent in their approaches in awarding the marks,” said Mahardale.

If certain markers need more assistance before marking the actual papers, then more guidance is provided, he added. “Because of that, we’re able to ensure a very rigorous, very thoughtful process that allows for students’ responses to be accepted.”

To ensure good subject knowledge, the markers deployed would be the respective subject teachers, nominated by the schools and the SEAB.

Beyond proficiency, Mahardale said it was important that markers are “flexible in their marking” so that they are “sensitive” to whether pupils show good conceptual understanding, which may not always be clear from the written answers.

Markers also specialise in “just a few” of the open-ended questions, based on the number of markers and the complexity of the question.

“Because we narrow (down) the questions that they’re marking, we don’t usually see markers who are more stringent than the others,” he added.

During the actual marking, markers will also find that some answers were not covered during the initial standardisation.

“If we find that these are possible answers that we should use to update our marking scheme, … we’ll update SEAB,” said Mahardale. “That’s how we evolve the marking scheme.”

This process can take place “very fast” because SEAB personnel will be on hand.

“They know that during … the first day of marking, there may be the possibility of a lot of queries from the key personnel as well as markers,” he said.

“They’re there to respond and to make a decision quickly about … applying any updates to the marking scheme across all the centres.”

As a control measure, random checks are done on 5 to 10 per cent of scripts using the on-screen marking system. If there are answers not marked accurately, “we’ll go to the markers, and we’ll have a conversation”, he said.

Those markers could have applied the marking scheme inaccurately.

“But we also want to hear from the markers (about) how they applied their understanding of that particular marking point to that question and that response,” said Mahardale.

Then we’ll come to a conclusion (about) whether … the student’s response shows a good conceptual understanding and we can give the marks.”

By and large, he added, “we do reach a consensus”.

The focus on conceptual understanding means the marking scheme focuses less on keywords in answers. The question on evaporation is an example.

But external tuition — or, in his words, “additional lessons outside of school” — might account for some parents’ “fixation” on keywords.

“They aren’t privy to the context of the learning environment in the school,” said Mahardale. “So when they’re helping the students to answer questions better, they tend to focus a lot on the keywords.”

But even as answers can be varied, “we’ve also got to strike a bit of a balance in terms of the level of scientific literacy”, he added.

He gave another example: For an exam question on the temperature of hot water in a cup, the expected answer would include the temperature unit.

“These are scientific literacy skills that I think our students mustn’t forego in the pursuit of allowing (them) to use their own terms in explaining scientific concepts,” he said.

WATCH: Diana gets real with Education Minister Chan Chun Sing about the PSLE (12:31)

When it comes to open-ended questions, there are two main types. The first tests pupils on basic knowledge. The second tests them on the application of that knowledge to different science scenarios.

Mahardale has realised that “many students may (find) the open-ended questions challenging” because some scenarios, to them, “might be very unique”.

“But what I always assure my teachers and my students as well is that … everything that you’re tested (on) is within the syllabus,” he said.

“Ask yourself: What concepts am I being tested (on) in this particular scenario?”

He encouraged pupils (and parents) to see science as a subject they can get better at when they are more curious about how things around them work.

“That’s when they’ll learn how to connect the concepts that they learn in the classroom to the scenarios that are presented to them in the open-ended questions,” he said.

Pupils are not marked down for poor spelling and grammar.

“What’s important is that our students are able to express themselves and … show clarity in the conceptual understanding that they’re trying to convey,” said Mahardale. If it is clear enough for the markers, “we’ll allocate marks to our students”.

In terms of marking maths papers, teachers do not only look at the final answer. Marks may be awarded for method even if the final answers are wrong.

“We do take a look at the whole response and see whether students have shown understanding in the method,” said Mahardale. This includes methods such as algebra and trigonometry, which would have been possible responses covered during the standardisation process.

If markers are unsure about certain solutions, they can discuss them with the key personnel. “If the students are able to show very good mathematical reasoning, … then I think we’re able to give the marks for that response,” he said.

He acknowledged that not all markers may be familiar with certain maths concepts — such as the Sakamoto method, an alternative to the model method for solving word problems.

“What I can assure everyone is that there is that conversation, and (teachers) will be able to lean on each other’s expertise to ensure that we have a good understanding about how to allocate those marks,” he said.

Mahardale also gave assurances that the PSLE is not getting more difficult. “A lot of the papers that we set … are very fair,” he said. “The demands are pegged (to) what we’d see in our primary school students.”

He described science questions that may stump some pupils as “interesting”, “creative” and “maybe out of the box”.

“The onus is on us to ensure that we give our students a breadth of knowledge (and) grow their curiosity,” he said, adding that there is also a need to build thinking skills.

“Once we’re able to do that, then our students will be (better) prepared (to) tackle such questions.”

Related articles:

In the case of maths, the overall standard of the question paper has been “kept consistent” over the years, according to the SEAB, as determined by “the mix of easy, average and challenging questions” in the paper.

Exam questions are set by a team of experienced teachers, plus specialists from the education ministry and the SEAB, who are “very familiar” with the primary school syllabuses and exam candidates’ “range of abilities”.

The exam will “comprehensively cover” the topics taught in school, with a “good spread of questions across the different topics of the syllabus over six years”, a spokesperson said. Among the maths topics are fractions, decimals, ratios, statistics and geometry.

What is important, said Mahardale, is to get pupils to “understand the expectations and … the standards of a formal examination”.

For him, a good rule of thumb is that “we should spend 80 per cent of our time making sure that our kids understand the concepts”, with the remaining time spent on teaching them the skills to tackle exam papers.

In his experience, pupils sometimes “try to cram (in) a lot of responses” to a given question.

This could be due to pupils “memorising information without applying it to the context of the question” and “hoping that we’ll pick up on some of these things”, said Mahardale.

But markers must ensure that “whatever that’s conveyed by the students doesn’t show any misconceptions as well”, he added.

“And if the students do show misconception, … we’d have to penalise the misconception.”

Instead of pupils regurgitating concepts, he would like them to answer to the question. They should also note that the marks allocated to the question are not necessarily indicative of how much to write.

“We need to teach our kids skills such as being able to discern the depth of questions and their responses,” he said. “If a question asks you for a definition, then it’s very straightforward.

But if the question asks you to explain why you observe certain phenomena, then you’ll be expecting the students to show understanding of the concept … in that question.”

He thinks it is important for pupils to analyse and better understand the scenarios in the questions.

“For example, you have a picture of an experimental set-up. They need to … see how this set-up is related to a concept that they’ve learnt,” he cited.

The way to do this — in any exam paper — is to take time to understand what kind of answer is expected, rather than “jump into responding too quickly”, he said.

“Looking at the demands of the paper that we have, I think there’s enough time for our students … to do that well.”

WATCH: Ask me anything with Singapore Education Minister Chan Chun Sing (7:27)