How the public appointments process is run and who plays a role in it.

07 OCT 2020 7 min read

This term usually applies to the whole range of appointments to public bodies. These range from the chairs of high-profile bodies like the BBC, or the governor of the Bank of England, to board members of small, technical advisory bodies. They can also include appointments to publicly funded bodies like museums or the NHS boards. The term does not cover civil service appointments.

Public appointments are generally made by ministers, though they can delegate this responsibility. High-profile positions often need the approval of No.10. There are established processes to ensure the prime minister gets advice – and this can slow the process down, with delays to the appointments process causing frustration, both to the bodies awaiting appointments and to the candidates applying for posts. The agreement of devolved ministers is sometimes also needed. In some cases the appointment is nominally made by the Queen – but this is always on advice from the government.

The system for making public appointments is set out by the government in its Governance Code for Public Appointments, 24 published in 2016. Bodies covered by this code are set out in an Order in Council. 25 The governance code superseded the previous code, which was owned by the commissioner for public appointments, following a review by Gerry, now Lord, Grimstone. Appointment processes for some roles, however, are set out in the legislation establishing the relevant body.

The public appointments process is run by the sponsoring department, which establishes an 'advisory assessment panel'. Roles must be advertised on the public appointments website 26 with a job description that sets out essential and desirable qualities. For some of the most important roles, headhunters and wider advertising will be employed. Once the deadline is reached, applications are sifted and a shortlist selected for interview by a panel, usually chaired by a senior official.

Panels must include one member who is independent of the department and the body concerned. For a list of high-profile bodies agreed with the commissioner on public appointments, there should be a senior independent panel member, who is not politically active, responsible for highlighting any material breaches of the code. The commissioner is consulted on who will take on that role.

The code makes it clear, as did the previous code, that ministers are to be consulted and involved at each stage of the process, and that the role of the assessment panel is to provide ministers with a list of appointable candidates – those who meet the criteria specified in the job description. It also makes clear that ministers can reject the whole list, and ask for a competition to be re-run, or even appoint a candidate that the panel has deemed unappointable.

If a minister wishes to appoint someone who has been found unappointable, the commissioner must be notified. This has not yet happened.

No. The Governance Code makes clear that ministers can, “in exceptional circumstances”, make appointments without a competition. In such a case they need to consult the commissioner for public appointments before the appointment has been announced publicly.

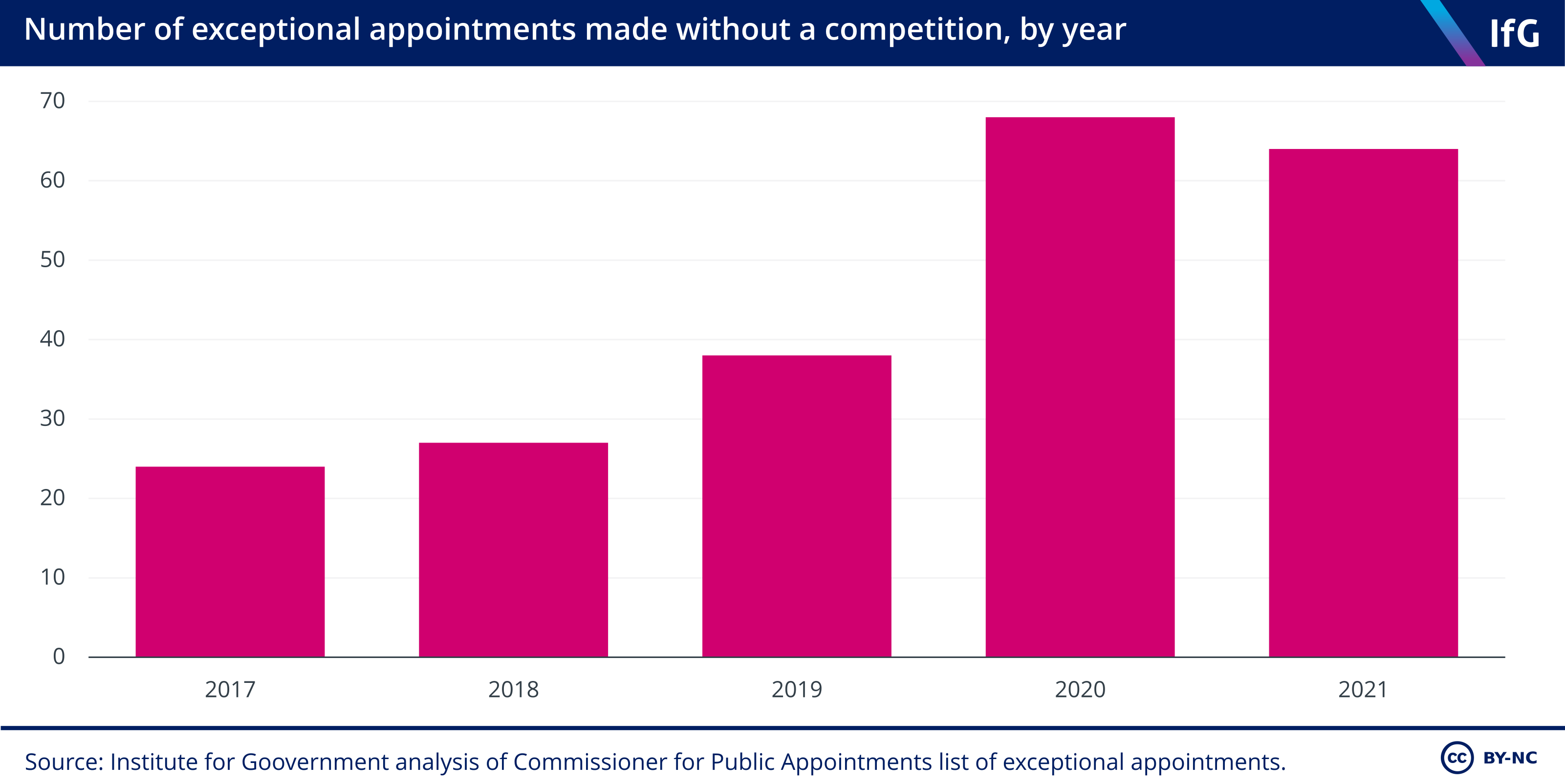

In the last full year, 2021, 64 appointments were made through this exceptional procedure by the UK and Welsh governments. 27 This was a slight fall on 2020, but much higher than any year between 2017 and 2019. In most cases, the reasons given centred on the need to make temporary appointments due to delayed appointments processes, to keep a body quorate or with a chair. Temporary appointments can be damaging when crucial bodies are without long-term leadership for a long time. For instance Ofcom, the media regulator, has been without a permanent chair for over a year. 28

The role of the commissioner’s office changed following the Grimstone review. Rather than setting the code, the commissioner now regulates public appointments against the government’s code. As set out in the Governance Code, there are circumstances in which the commissioner must be consulted in advance by ministers, but the commissioner’s role is to audit departments against the Code, report annually and thematically on compliance with the processes and principles set out in the Code, and to investigate complaints. Before these changes, the commissioner owned the Code and worked with a team of centrally appointed assessors who acted as independent members of panels.

The commissioner regulates appointments by the UK government and the Welsh government. Appointments to more than 300 UK bodies and 55 Welsh government bodies fall within his remit.

Parliament’s role is confined to pre-appointment hearings for preferred candidates to chair more than 50 key public bodies. The list of bodies subject to select committee pre-appointment scrutiny is determined against criteria set out in Cabinet Office guidance. 33 Parliament cannot veto these appointments. There have been cases where a candidate has withdrawn when it has become clear a select committee would recommend against their appointment – but in other cases, ministers have proceeded to appoint notwithstanding an adverse view from the select committee. Examples include the appointment of Amanda Spielman to head Ofsted 34 and the appointment of Baroness Stowell to chair the Charity Commission. 35

There are exceptions. The legislation establishing the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) gave the Treasury Select Committee a veto over the appointment of the chair and members of the Budget Responsibility Committee 36 , in a move designed to underline the OBR’s independence. In the case of parliamentary bodies – like the National Audit Office, parliament leads the process of appointing the chair and the appointment is jointly made by the prime minister and the chair of the Public Accounts Committee.

Ministers should comply with the principles and processes for public appointments set out in the Governance Code, but otherwise are free to appoint who they want – but they are accountable to parliament for the appointments they make.

Ministers. Pay varies enormously between public bodies. A few chairs and chief executives are paid well in excess of the prime minister’s salary, while many others are unpaid or paid nominal amounts.

Yes. The Governance Code establishes a presumption that chairs serve a maximum of two terms or 10 years, and often ministers will simply make a change when a chair’s term ends. But ministers can also dismiss chairs of public bodies. The exception, again, is the OBR, where the consent of the Treasury Select Committee is needed if the chancellor decides to dismiss the chair or a member of the Budget Responsibility Committee.

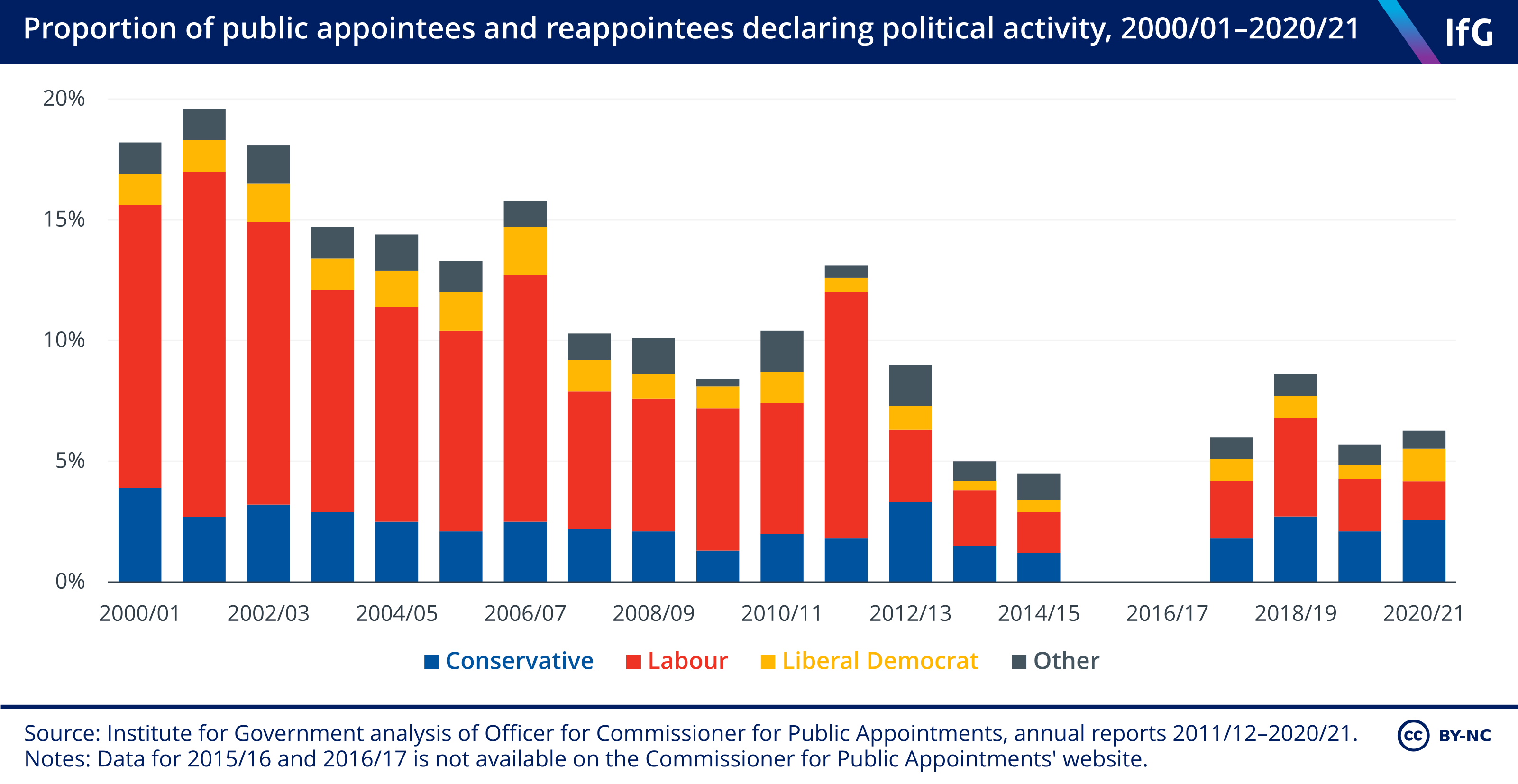

Candidates are required to declare political activity, that is candidacy for, employment by or donations to a political party, but it is not a barrier to appointment. A minority of public appointees declare that they are politically active – the latest OCPA report says that of those who answered the question on political activity, only 6.2% of those appointed or reappointed in 2020/21 declared any such activity.

However, for the first time since 2012/13, there were more politically active public appointees from the Conservative Party than from Labour. This trend was particularly striking among new chairs appointed: of those who declared themselves to be politically active, eight out of nine were Conservatives.

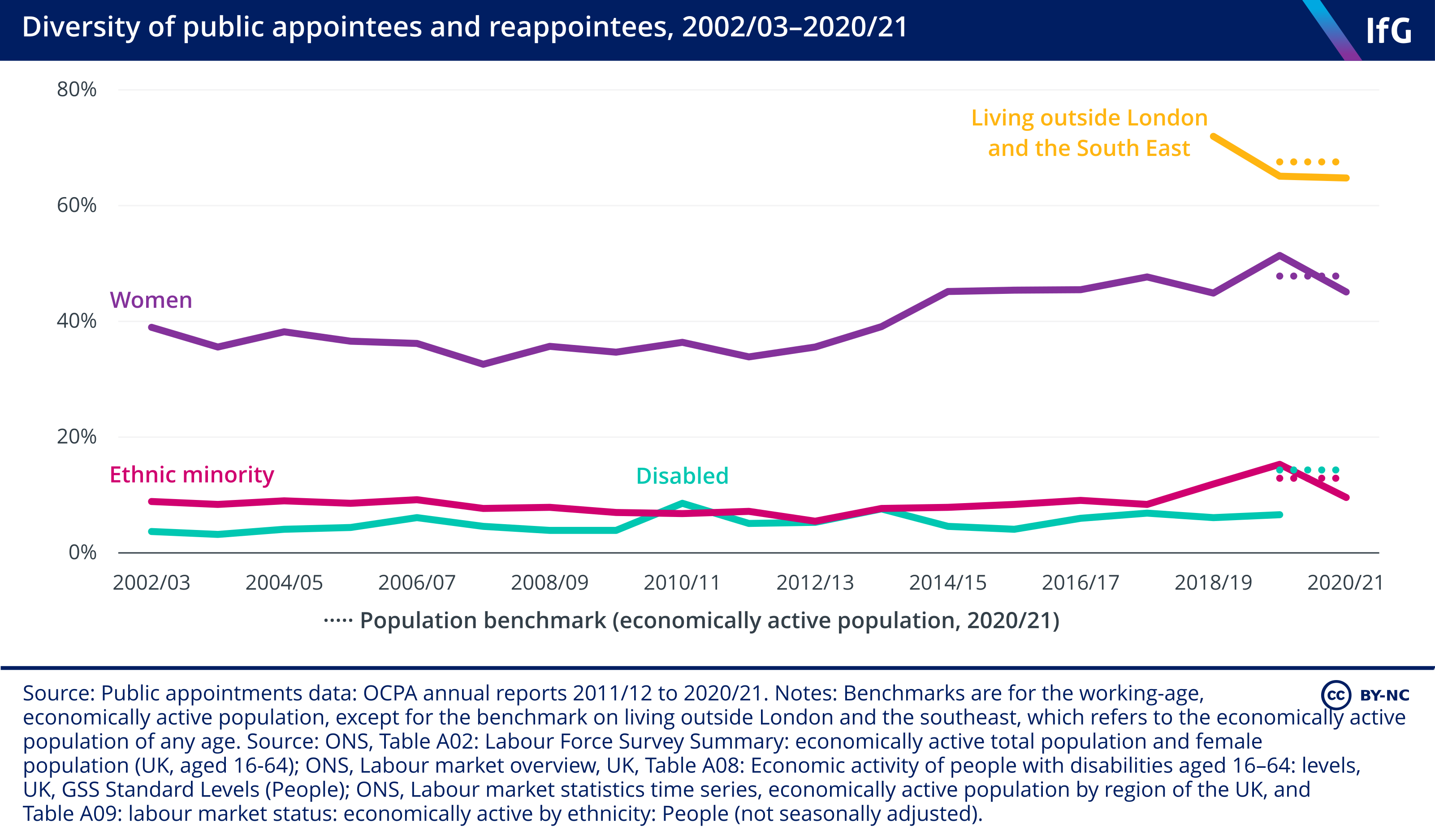

Improving the diversity of public boards has been a major focus for successive governments. Diversity is monitored by the commissioner for public appointments.

The most recent data from the commissioner showed that in 2020/21: